Recently a friend of mine forwarded an email to me about a Wi-fi service he wanted to use from a firm, but he raised some technical questions with them which they seemed to completely misunderstand!

So, let’s talk about the misconceptions of Wi-fi passwords.

Many people assume that when you log into a system, it means that system is secure. For example, logging into a website makes sure that your data is secure and protected, right? Not necessarily – the password you entered could be on a web page that is not secured by TLS, or perhaps the web server doesn’t properly transfer it’s contents to a database. Maybe the website was badly written, and means it’s vulnerable to one of a handful of common attacks (with fun names like “Cross Site Scripting” or “SQL Injection Attacks”)…

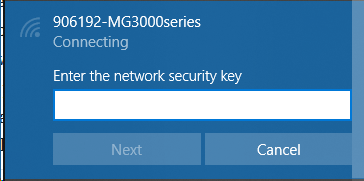

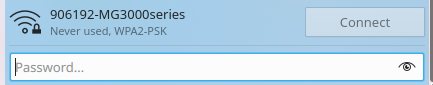

People also assume the same thing about Wi-fi. You reached a log in page, so it must be secure, right? It depends. If you didn’t put in a password to access the Wi-fi in the first place (like in the image of the Windows 10 screen, or on my KDE Desktop) then you’re probably using Unsecured Wi-fi.

People like to compare network traffic to “sending things through the post”, notablycomparing E-Mail to “sending a postcard”, versus PGP encrypted E-Mail being compared to “sending a sealed letter”. Unencrypted Wi-fi is like using CB. Anyone who can hear your signal can understand what you are saying… but if you visit a website which uses HTTPS, then it’s like listening to someone saying random numbers over the radio.

And, if you’re using Unencrypted Wi-fi, it’s also possible for an attacker to see what website you visited, because the request for the address to reach on the Internet (e.g. “Google.com” = 172.217.23.14) is sent in the clear. Also because of the way that DNS works (that name to address matching thing) means that if someone knows you’re visiting a “site of interest” (like, perhaps a bank website), they can reply *before* the real DNS server, and tell you that the server on their machine is actually your bank’s website.

So, many of these things can be protected against by using a simple method, that many people who provide Wi-fi don’t do.

Turn on WPA2 (the authentication bit). Even if *everyone* uses the same password (which they’d have to for WPA2), the fact you’re logging into the Access Point means it creates a unique shared secret for your session.

“But hang on”, I hear the guy at the back cry, “you used the same password – how does that work?”

OK, so this is where the fun stuff starts. The password is just part of how you negotiate to get on to the network. There’s a complex beast of a method that explains how get a shared unique secret when you’re passing stuff around “in the clear”, and so as a result, when you first connect to that Wi-fi access point, and you hand over your password, it “Authorises” you on to the network, but then hands you over to the encryption part, where you generate a key and then use that to talk to each other. The encryption is the bit like “HTTPS”, where you make it so that people can’t see what you’re looking at.

“I got told that if everyone used the same password” said a hipster in the front row, “I wouldn’t be able to tell them apart.” Aha, not true. You can have a separate passphrase to access the Wi-fi from the Login page, after all, you’ve got to make sure that people aren’t breaking the rules (which they *TOTALLY* read, before clicking “I agree, just get me on the damn Wi-fi already”) by using your network.

“OK”, says the lady over on the right, “but when I connected to the Wi-fi, they asked me to log in using Facebook – that’s secure, right?”

Um, no. Well, maybe. See, if they gave you a WPA2 password to log into the Wi-fi, and then the first thing you got to was that login screen, then yep, it’s all good! {*} You can browse with (relative) impunity. But if they didn’t… well, not only are they asking you to shout your secrets on the radio, but if you’re really unlucky, the page asking you to log into Facebook might *also* not actually be Facebook, but another website that just looks like Facebook… after all, I’m sure that page you went to complained that it wasn’t Google or Facebook when you tried to open it…

{*} Except for the fact they’re asking you to tell them not only who you are, but who you’re also friends with, where you went to school, what your hobbies are, what groups you’re in, your date of birth and so on.

But anyway. I understand why those login screens are there. They’re asserting that not only do you understand that you mustn’t use their network for bad things, but that if the police come and ask them who used their network to do something naughty, they can say “He said his name was ‘Bob Smith’ and his email address was ‘bob@example.com’, Officer”…

It also means that the “free” service they provide to you, usually at some great expense (*eye roll*) can get them some return on investment (like, they just got your totally-real-and-not-at-all-made-up-email-address… honest, and they also know what websites you visited while you were there, which they can sell on).

So… What to do the next time you “need” Wi-fi, and there’s a free service there? Always use a VPN when you’re not using a network you trust. If the Wi-fi isn’t using WPA2 encryption (even something as simple as “Buy a drink first” is a great passphrase to use!) point them to this page, and tell them it’s virtually pain free (as long as the passphrase is easy to remember, easy to type and doesn’t have too many weird symbols in) and makes their service more safe and secure for their customers…

Featured image is “Wifi Here on a Blackboard” by “Jem Stone” on Flickr and is released under a CC-BY license.

Occasionally I have seen the password in the SSID like “Coffee Shop pw: flatwhite” so you don’t have to ask, or find the notice to connect to the WiFi.I think this is good.

Yehr, that’s a nice way to do it!