In Ansible 2.10, Ansible started bundling modules and plugins as “Collections”, basically meaning that Ansible didn’t need to make a release every time a vendor wanted to update the libraries it required, or API changes required new fields to be supplied to modules. As part of this split between “Collections” and “Core”, the AWS modules and plugins got moved into a collection.

Now, if you’re using Ansible 2.9 or earlier, this probably doesn’t impact you, but there are some nice features in Ansible 2.10 that I wanted to use, so… buckle up :)

Getting started with Ansible 2.10, using a virtual environment

If you currently are using Ansible 2.9, it’s probably worth creating a “python virtual environment”, or “virtualenv” to try out Ansible 2.10. I did this on my Ubuntu 20.04 machine by typing:

sudo apt install -y virtualenv

mkdir -p ~/bin

cd ~/bin

virtualenv -p python3 ansible_2.10

The above ensures that you have virtualenv installed, creates a directory called “bin” in your home directory, if it doesn’t already exist, and then places the virtual environment, using Python3, into a directory there called “ansible_2.10“.

Whenever we want to use this new environment you must activate it, using this command:

source ~/bin/ansible_2.10/bin/activate

Once you’ve executed this, any binary packages created in that virtual environment will be executed from there, in preference to the file system packages.

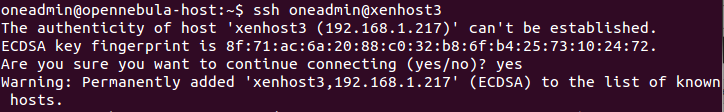

You can tell that you’ve “activated” this virtual environment, because your prompt changes from user@HOST:~$ to (ansible_2.10) user@HOST:~$ which helps 😀

Next, let’s create a requirements.txt file. This will let us install the environment in a repeatable manner (which is useful with Ansible). Here’s the content of this file.

ansible>=2.10

boto3

botocore

So, this isn’t just Ansible, it’s also the supporting libraries we’ll need to talk to AWS from Ansible.

We execute the following command:

pip install -r requirements.txt

Note, on Windows Subsystem for Linux version 1 (which I’m using) this will take a reasonable while, particularly if it’s crossing from the WSL environment into the Windows environment, depending on where you have specified the virtual environment to be placed.

If you get an error message about something to do with being unable to install ffi, then you’ll need to install the package libffi-dev with sudo apt install -y libffi-dev and then re-run the pip install command above.

Once the installation has completed, you can run ansible --version to see something like the following:

ansible 2.10.2

config file = None

configured module search path = ['/home/user/.ansible/plugins/modules', '/usr/share/ansible/plugins/modules']

ansible python module location = /home/user/ansible_2.10/lib/python3.8/site-packages/ansible

executable location = /home/user/ansible_2.10/bin/ansible

python version = 3.8.2 (default, Jul 16 2020, 14:00:26) [GCC 9.3.0]

Configuring Ansible for local collections

Ansible relies on certain paths in the filesystem to store things like collections, roles and modules, but I like to circumvent these things – particularly if I’m developing something, or moving from one release to the next. Fortunately, Ansible makes this very easy, using a single file, ansible.cfg to tell the code that’s running in this path where to find things.

A quick note on File permissions with ansible.cfg

Note that the POSIX file permissions for the directory you’re in really matter! It must be set to 775 (-rwxrwxr-x) as a maximum – if it’s “world writable” (the last number) it won’t use this file! Other options include 770, 755. If you accidentally set this as world writable, or are using a directory from the “Windows” side of WSL, then you’ll get an error message like this:

[WARNING]: Ansible is being run in a world writable directory (/home/user/ansible_2.10_aws), ignoring it as an ansible.cfg source. For more information see

https://docs.ansible.com/ansible/devel/reference_appendices/config.html#cfg-in-world-writable-dir

That link is this one: https://docs.ansible.com/ansible/devel/reference_appendices/config.html#cfg-in-world-writable-dir and has some useful advice.

Back to configuring Ansible

In ansible.cfg, I have the following configured:

[defaults]

collections_paths = ./collections:~/.ansible/collections:/usr/share/ansible/collections

This file didn’t previously exist in this directory, so I created that file.

This block asks Ansible to check the following paths in order:

collections in this path (e.g. /home/user/ansible_2.10_aws/collections)collections in the .ansible directory under the user’s home directory (e.g. /home/user/.ansible/collections)- and finally

/usr/share/ansible/collections for system-wide collections.

If you don’t configure Ansible with the ansible.cfg file, the default is to store the collections in ~/.ansible/collections, but you can “only have one version of the collection”, so this means that if you’re relying on things not to change when testing, or if you’re running multiple versions of Ansible on your system, then it’s safest to store the collections in the same file tree as you’re working in!

Installing Collections

Now we have Ansible 2.10 installed, and our Ansible configuration file set up, let’s get our collection ready to install. We do this with a requirements.yml file, like this:

---

collections:

- name: amazon.aws

version: ">=1.2.1"

What does this tell us? Firstly, that we want to install the Amazon AWS collection from Ansible Galaxy. Secondly that we want at least the most current version (which is currently version 1.2.1). If you leave the version line out, it’ll get “the latest” version. If you replace ">=1.2.1" with 1.2.1 it’ll install exactly that version from Galaxy.

If you want any other collections, you add them as subsequent lines (more details here), like this:

collections:

- name: amazon.aws

version: ">=1.2.1"

- name: some.other

- name: git+https://example.com/someorg/somerepo.git

version: 1.0.0

- name: git@example.com:someorg/someotherrepo.git

Once we’ve got this file, we run this command to install the content of the requirements.yml: ansible-galaxy collection install -r requirements.yml

In our case, this installs just the amazon.aws collection, which is what we want. Fab!

Getting our dynamic inventory

Right, so we’ve got all the pieces now that we need! Let’s tell Ansible that we want it to ask AWS for an inventory. There are three sections to this.

Configuring Ansible, again!

We need to open up our ansible.cfg file. Because we’re using the collection to get our Dynamic Inventory plugin, we need to tell Ansible to use that plugin. Edit ./ansible.cfg in your favourite editor, and add this block to the end:

[inventory]

enable_plugins = aws_ec2

If you previously created the ansible.cfg file when you were setting up to get the collection installed alongside, then your ansible.cfg file will look (something) like this:

[defaults]

collections_paths = ./collections:~/.ansible/collections:/usr/share/ansible/collections

[inventory]

enable_plugins = amazon.aws.aws_ec2

Configure AWS

Your machine needs to have access tokens to interact with the AWS API. These are stored in ~/.aws/credentials (e.g. /home/user/.aws/credentials) and look a bit like this:

[default]

aws_access_key_id = A1B2C3D4E5F6G7H8I9J0

aws_secret_access_key = A1B2C3D4E5F6G7H8I9J0a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8i9j0

Set up your inventory

In a bit of a change to how Ansible usually does the inventory, to have a plugin based dynamic inventory, you can’t specify a file any more, you have to specify a directory. So, create the file ./inventory/aws_ec2.yaml (having created the directory inventory first). The file contains the following:

---

plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2

Late edit 2020-12-01: Further to the comment by Giovanni, I’ve amended this file snippet from plugin: aws_ec2 to plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2.

By default, this just retrieves the hostnames of any running EC2 instance, as you can see by running ansible-inventory -i inventory --graph

@all:

|--@aws_ec2:

| |--ec2-176-34-76-187.eu-west-1.compute.amazonaws.com

| |--ec2-54-170-131-24.eu-west-1.compute.amazonaws.com

| |--ec2-54-216-87-131.eu-west-1.compute.amazonaws.com

|--@ungrouped:

I need a bit more detail than this – I like to use the tags I assign to AWS assets to decide what I’m going to target the machines with. I also know exactly which regions I’ve got my assets in, and what I want to use to get the names of the devices, so this is what I’ve put in my aws_ec2.yaml file:

---

plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2

keyed_groups:

- key: tags

prefix: tag

- key: 'security_groups|json_query("[].group_name")'

prefix: security_group

- key: placement.region

prefix: aws_region

- key: tags.Role

prefix: role

regions:

- eu-west-1

hostnames:

- tag:Name

- dns-name

- public-ip-address

- private-ip-address

Late edit 2020-12-01: Again, I’ve amended this file snippet from plugin: aws_ec2 to plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2.

Now, when I run ansible-inventory -i inventory --graph, I get this output:

@all:

|--@aws_ec2:

| |--euwest1-firewall

| |--euwest1-demo

| |--euwest1-manager

|--@aws_region_eu_west_1:

| |--euwest1-firewall

| |--euwest1-demo

| |--euwest1-manager

|--@role_Firewall:

| |--euwest1-firewall

|--@role_Firewall_Manager:

| |--euwest1-manager

|--@role_VM:

| |--euwest1-demo

|--@security_group_euwest1_allow_all:

| |--euwest1-firewall

| |--euwest1-demo

| |--euwest1-manager

|--@tag_Name_euwest1_firewall:

| |--euwest1-firewall

|--@tag_Name_euwest1_demo:

| |--euwest1-demo

|--@tag_Name_euwest1_manager:

| |--euwest1-manager

|--@tag_Role_Firewall:

| |--euwest1-firewall

|--@tag_Role_Firewall_Manager:

| |--euwest1-manager

|--@tag_Role_VM:

| |--euwest1-demo

|--@ungrouped:

To finish

Now you have your dynamic inventory, you can target your playbook at any of the groups listed above (like role_Firewall, aws_ec2, aws_region_eu_west_1 or some other tag) like you would any other inventory assignment, like this:

---

- hosts: role_Firewall

gather_facts: false

tasks:

- name: Show the name of this device

debug:

msg: "{{ inventory_hostname }}"

And there you have it. Hope this is useful!

Late edit: 2020-11-23: Following a conversation with Andy from Work, we’ve noticed that if you’re trying to do SSM connections, rather than username/password based ones, you might want to put this in your aws_ec2.yml file:

---

plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2

hostnames:

- tag:Name

compose:

ansible_host: instance_id

ansible_connection: 'community.aws.aws_ssm'

Late edit 2020-12-01: One final instance, I’ve changed plugin: aws_ec2 to plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2.

This will keep your hostnames “pretty” (with whatever you’ve tagged it as), but will let you connect over SSM to the Instance ID. Good fun :)

Featured image is “inventory” by “Lee” on Flickr and is released under a CC-BY-SA license.