A love letter to Ansible Tower

I love Ansible… I mean, I really love Ansible. You can ask anyone, and they’ll tell you my first love is my wife, then my children… and then it’s Ansible.

OK, maybe it’s Open Source and then Ansible, but either way, Ansible is REALLY high up there.

But, while I love Ansible, I love what Ansible Tower brings to an environment. See, while you get to easily and quickly manage a fleet of machines with Ansible, Ansible Tower gives you the fine grained control over what you need to expose to your developers, your ops team, or even, in a fit of “what-did-you-just-do”-ness, your manager. (I should probably mention that Ansible Tower is actually part of a much larger portfolio of products, called Ansible Automation Platform, and there’s some hosted SaaS stuff that goes with it… but the bit I really want to talk about is Tower, so I’ll be talking about Tower and not Ansible Automation Platform. Sorry!)

Ansible Tower has a scheduling engine, so you can have a “Go” button, for deploying the latest software to your fleet, or just for the 11PM patching cycle. It has a credential store, so your teams can’t just quickly go and perform an undocumented quick fix on that “flaky” box – they need to do their changes via Ansible. And lastly, it has an inventory, so you can see that the last 5 jobs failed to deploy on that host, so maybe you’ve got a problem with it.

One thing that people don’t so much love to do, is to get a license to deploy Tower, particularly if they just want to quickly spin up a demonstration for some colleagues to show how much THEY love Ansible. And for those people, I present AWX.

The first hit is free

One of the glorious and beautiful things that RedHat did, when they bought Ansible, was to make the same assertion about the Ansible products that they make to the rest of their product line, which is… while they may sell a commercial product, underneath it will be an Open Source version of that product, and you can be part of developing and improving that version, to help improve the commercial product. Thus was released AWX.

Now, I hear the nay-sayers commenting, “but what if you have an issue with AWX at 2AM, how do you get support on that”… and to those people, I reply: “If you need support at 2AM for your box, AWX is not the tool for you – what you need is Tower.”… Um, I mean Ansible Automation Platform. However, Tower takes a bit more setting up than what I’d want to do for a quick demo, and it has a few more pre-requisites. ANYWAY, enough about dealing with the nay-sayers.

AWX is an application inside Docker containers. It’s split into three parts, the AWX Web container, which has the REST API. There’s also a PostgreSQL database inside there too, and one “Engine”, which is the separate container which gets playbooks from your version control system, asks for any dynamic inventories, and then runs those playbooks on your inventories.

I like running demos of Tower, using AWX, because it’s reasonably easy to get stood up, and it’s reasonably close to what Tower looks and behaves like (except for the logos)… and, well, it’s a good gateway to getting people interested in what Tower can do for them, without them having to pay (or spend time signing up for evaluation licenses) for the environment in the first place.

And what’s more, it can all be automated

Yes, folks, because AWX is just a set of docker containers (and an install script), and Ansible knows how to start Docker containers (and run an install script), I can add an Ansible playbook to my cloud-init script, Vagrantfile or, let’s face it, when things go really wrong, put it in a bash script for some poor keyboard jockey to install for you.

If you’re running a demo, and you don’t want to get a POC (proof of concept) or evaluation license for Ansible Tower, then the chances are you’re probably not running this on RedHat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) either. That’s OK, once you’ve sold the room on using Tower (by using AWX), you can sell them on using RHEL too. So, I’ll be focusing on using CentOS 8 instead. Partially because there’s a Vagrant box for CentOS 8, but also because I can also use CentOS 8 on AWS, where I can prove that the Ansible Script I’m putting into my Vagrantfile will also deploy nicely via Cloud-Init too. With a very small number of changes, this is likely to work on anything that runs Docker, so everything from Arch to Ubuntu… probably 😁

“OK then. How can you work this magic, eh?” I hear from the back of the room. OK, pipe down, nay-sayers.

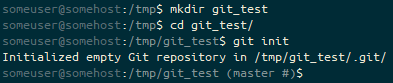

First, install Ansible on your host. You just need to run dnf install -y ansible.

Next, you need to install Docker. This is a marked difference between AWX and Ansible Tower, as AWX is based on Docker, but Ansible Tower uses other magic to make it work. When you’re selling the benefits of Tower, note that it’s not a 1-for-1 match at this point, but it’s not a big issue. Fortunately, CentOS can install Docker Community edition quite easily. At this point, I’m swapping to using Ansible playbooks. At the end, I’ll drop a link to where you can get all this in one big blob… In fact, we’re likely to use it with our Cloud-Init deployment.

Aw yehr, here’s the good stuff

tasks:

- name: Update all packages

dnf:

name: "*"

state: latest

- name: Add dependency for "yum config-manager"

dnf:

name: yum-utils

state: present

- name: Add the Docker Repo

shell: yum config-manager --add-repo https://download.docker.com/linux/centos/docker-ce.repo

args:

creates: /etc/yum.repos.d/docker-ce.repo

warn: false

- name: Install Docker

dnf:

name:

- docker-ce

- docker-ce-cli

- containerd.io

state: present

notify: Start Docker

That first stanza – update all packages? Well, that’s because containerd.io relies on a newer version of libseccomp, which hasn’t been built in the CentOS 8 Vagrantbox I’m using.

The next one? That ensures I can run yum config-manager to add a repo. I could use the copy module in Ansible to create the repo files so yum and/or dnf could use that instead, but… meh, this is a single line shell command.

And then we install the repo, and the docker-ce packages we require. We use the “notify” statement to trigger a handler call to start Docker, like this:

handlers:

- name: Start Docker

systemd:

name: docker

state: started

Fab. We’ve got Docker. Now, let’s clone the AWX repo to our machine. Again, we’re doing this with Ansible, naturally :)

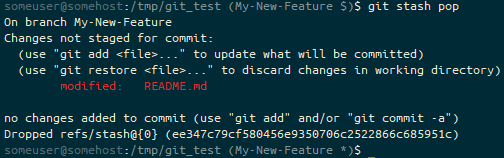

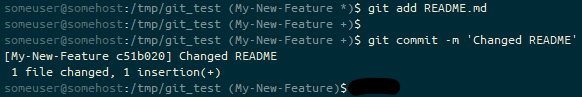

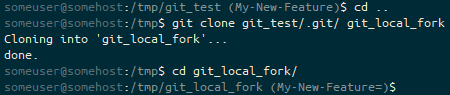

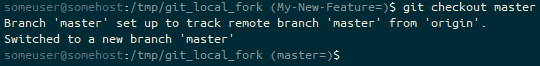

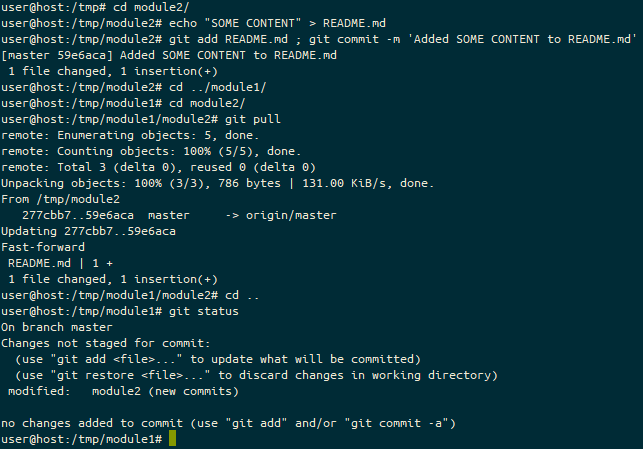

tasks:

- name: Clone AWX repo to local path

git:

repo: https://github.com/ansible/awx.git

dest: /opt/awx

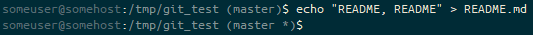

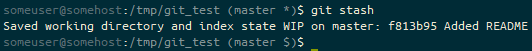

- name: Get latest AWX tag

shell: |

if [ $(git status -s | wc -l) -gt 0 ]

then

git stash >/dev/null 2>&1

fi

git fetch --tags && git describe --tags $(git rev-list --tags --max-count=1)

if [ $(git stash list | wc -l) -gt 0 ]

then

git stash pop >/dev/null 2>&1

fi

args:

chdir: /opt/awx

register: latest_tag

changed_when: false

- name: Use latest released version of AWX

git:

repo: https://github.com/ansible/awx.git

dest: /opt/awx

version: "{{ latest_tag.stdout }}"

OK, there’s a fair bit to get from this, but essentially, we clone the repo from Github, then ask (using a collection of git commands) for the latest released version (yes, I’ve been bitten by just using the head of “devel” before), and then we check out that released version.

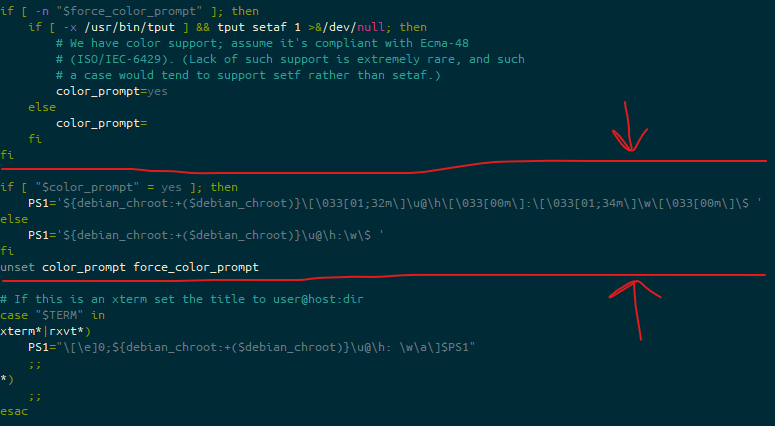

Fab, now we can configure it.

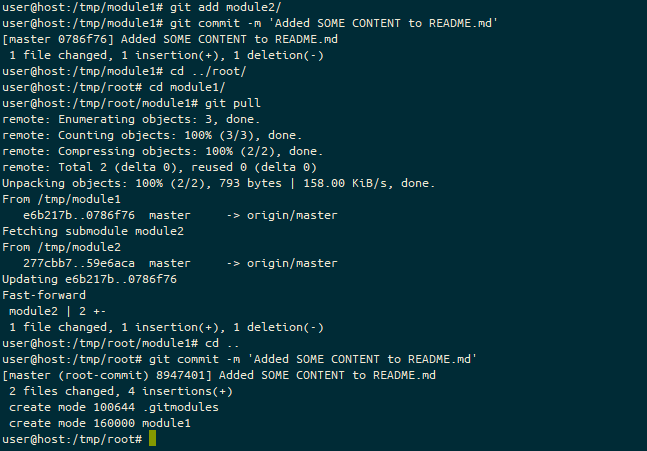

tasks:

- name: Set or Read admin password

set_fact:

admin_password_was_generated: "{{ (admin_password is defined or lookup('env', 'admin_password') != '') | ternary(false, true) }}"

admin_password: "{{ admin_password | default (lookup('env', 'admin_password') | default(lookup('password', 'pw.admin_password chars=ascii_letters,digits length=20'), true) ) }}"

- name: Configure AWX installer

lineinfile:

path: /opt/awx/installer/inventory

regexp: "^#?{{ item.key }}="

line: "{{ item.key }}={{ item.value }}"

loop:

- key: "awx_web_hostname"

value: "{{ ansible_fqdn }}"

- key: "pg_password"

value: "{{ lookup('password', 'pw.pg_password chars=ascii_letters,digits length=20') }}"

- key: "rabbitmq_password"

value: "{{ lookup('password', 'pw.rabbitmq_password chars=ascii_letters,digits length=20') }}"

- key: "rabbitmq_erlang_cookie"

value: "{{ lookup('password', 'pw.rabbitmq_erlang_cookie chars=ascii_letters,digits length=20') }}"

- key: "admin_password"

value: "{{ admin_password }}"

- key: "secret_key"

value: "{{ lookup('password', 'pw.secret_key chars=ascii_letters,digits length=64') }}"

- key: "create_preload_data"

value: "False"

loop_control:

label: "{{ item.key }}"

If we don’t already have a password defined, then create one. We register the fact we’ve had to create one, as we’ll need to tell ourselves it once the build is finished.

After that, we set a collection of values into the installer – the hostname, passwords, secret keys and so on. It loops over a key/value pair, and passes these to a regular expression rewrite command, so at the end, we have the settings we want, without having to change this script between releases.

When this is all done, we execute the installer. I’ve seen this done two ways. In an ideal world, you’d throw this into an Ansible shell module, and get it to execute the install, but the problem with that is that the AWX install takes quite a while, so I’d much rather actually be able to see what’s going on… and so, instead, we exit our prepare script at this point, and drop back to the shell to run the installer. Let’s look at both options, and you can decide which one you want to do. In my script, I’m doing the first, but just because it’s a bit neater to have everything in one place.

- name: Run the AWX install.

shell: ansible-playbook -i inventory install.yml

args:

chdir: /opt/awx/installer

cd /opt/awx/installer

ansible-playbook -i inventory install.yml

When this is done, you get a prepared environment, ready to access using the username admin and the password of … well, whatever you set admin_password to.

AWX takes a little while to stand up, so you might want to run this next Ansible stanza to see when it’s ready to go.

- name: Test access to AWX

tower_user:

tower_host: "http://{{ ansible_fqdn }}"

tower_username: admin

tower_password: "{{ admin_password }}"

email: "admin@{{ ansible_fqdn }}"

first_name: "admin"

last_name: ""

password: "{{ admin_password }}"

username: admin

superuser: yes

auditor: no

register: _result

until: _result.failed == false

retries: 240 # retry 240 times

delay: 5 # pause for 5 sec between each try

The upshot to using that command there is that it sets the email address of the admin account to “admin@your.awx.example.org“, if the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) of your machine is your.awx.example.org.

Moving from the Theoretical to the Practical

Now we’ve got our playbook, let’s wrap this up in both a Vagrant Vagrantfile and a Terraform script, this means you can deploy it locally, to test something internally, and in “the cloud”.

To simplify things, and because the version of Ansible deployed on the Vagrant box isn’t the one I want to use, I am using a single “user-data.sh” script for both Vagrant and Terraform. Here that is:

#!/bin/bash

if [ -e "$(which yum)" ]

then

yum install git python3-pip -y

pip3 install ansible docker docker-compose

else

echo "This script only supports CentOS right now."

exit 1

fi

git clone https://gist.github.com/JonTheNiceGuy/024d72f970d6a1c6160a6e9c3e642e07 /tmp/Install_AWX

cd /tmp/Install_AWX

/usr/local/bin/ansible-playbook Install_AWX.yml

While they both have their differences, they both can execute a script once the machine has finished booting. Let’s start with Vagrant.

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "centos/8"

config.vm.provider :virtualbox do |v|

v.memory = 4096

end

config.vm.provision "shell", path: "user-data.sh"

config.vm.network "forwarded_port", guest: 80, host: 8080, auto_correct: true

end

To boot this up, once you’ve got Vagrant and Virtualbox installed, run vagrant up and it’ll tell you that it’s set up a port forward from the HTTP port (TCP/80) to a “high” port – TCP/8080. If there’s a collision (because you’re running something else on TCP/8080), it’ll tell you what port it’s forwarded the HTTP port to instead. Once you’ve finished, run vagrant destroy to shut it down. There are lots more tricks you can play with Vagrant, but this is a relatively quick and easy one. Be aware that you’re not using HTTPS, so traffic to the AWX instance can be inspected, but if you’re running this on your local machine, it’s probably not a big issue.

How about running this on a cloud provider, like AWS? We can use the exact same scripts – both the Ansible script, and the user-data.sh script, using Terraform, however, this is a little more complex, as we need to create a VPC, Internet Gateway, Subnet, Security Group and Elastic IP before we can create the virtual machine. What’s more, the Free Tier (that “first hit is free” thing that Amazon Web Services provide to you) does not have enough horsepower to run AWX, so, if you want to look at how to run up AWX in EC2 (or to tweak it to run on Azure, GCP, Digital Ocean or one of the fine offerings from IBM or RedHat), then click through to the gist I’ve put all my code from this post into. The critical lines in there are to select a “CentOS 8” image, open HTTP and SSH into the machine, and to specify the user-data.sh file to provision the machine. Everything else is cruft to make the virtual machine talk to, and be seen by, hosts on the Internet.

To run this one, you need to run terraform init to load the AWS plugin, then terraform apply. Note that this relies on having an AWS access token defined, so if you don’t have them set up, you’ll need to get that sorted out first. Once you’ve finished with your demo, you should run terraform destroy to remove all the assets created by this terraform script. Again, when you’re running that demo, note that you ONLY have HTTP access set up, not HTTPS, so don’t use important credentials on there!

Once you’ve got your AWX environment running, you’ve got just enough AWX there to demo what Ansible Tower looks like, what it can bring to your organisation… and maybe even convince them that it’s worth investing in a license, rather than running AWX in production. Just in case you have that 2AM call-out that we all dread.

Featured image is “pharmacy” by “Tim Evanson” on Flickr and is released under a CC-BY-SA license.