I started thinking a couple of weeks ago, when my coding laptop broke, that it would be really useful to have a development machine somewhere else that I could use.

It wouldn’t need a lot of power (after all, I’m mostly developing web apps and not compiling stuff), but it does need to be a desktop OS, as I rather like being able to open code editors and suchlike, while I’ve got a web browser open.

I have an Android tablet, which while it’s great for being a tablet, it’s not much use as a desktop, and … yes, I’ve got a work laptop, but I don’t really want to install software on that (and I don’t think my admin team would be happy if I did).

Also, I quite like Linux.

Some time ago, I spotted that AWS has a “Virtual Desktop” environment, and I think that’s kinda what I’m after. Something I can spin up, run for a bit and then shut it down, so I thought I’d build something like that… but not pesky Windows, after all… who likes Windows, eh? ;)

So, I built a Virtual Desktop Environment (VDE) in AWS, using Terraform and a bit of shell script!

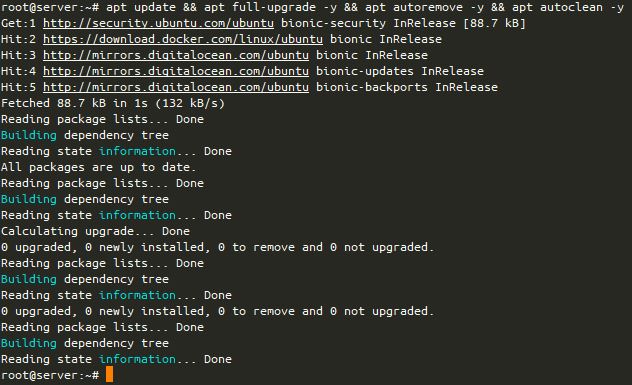

I start from an Ubuntu 18.04 server image, and, after the install is complete, I run this user-data script inside it. Yes, I know I could be doing this with Ansible, but… eh, I wanted it to be a quick deployment ;)

Oh, and there’s a couple of Terraform managed variables in here – ${aws_eip.vde.public_ip} is the AWS public IP address assigned to this host., ${var.firstuser} is the username we want to rename “ubuntu” (the stock server username) to. ${var.firstgecos} is the user’s “real name” which the machine identifies the user as (like “Log out Jon Spriggs” and so on). ${var.userpw} is either the password you want it to use, OR (by default) pwgen 12 which generates a 12 character long password. ${var.desktopenv} is the name of the desktop environment I want to install (Ubuntu by default) and … well, ${var.var_start} is a bit of a fudge, because I couldn’t, in a hurry, work out how to tell Terraform not to mangle the bash variable allocation of ${somevar} which is the format that Terraform also uses. D’oh.

#! /bin/bash

#################

# Set Hostname

#################

hostnamectl set-hostname vde.${aws_eip.vde.public_ip}.nip.io

#################

# Change User

#################

user=${var.firstuser}

if [ ! "$user" == 'ubuntu' ]

then

until usermod -c "${var.firstgecos}" -l $user ubuntu ; do sleep 5 ; done

until groupmod -n $user ubuntu ; do sleep 5 ; done

until usermod -d /home/$user -m $user ; do sleep 5 ; done

if [ -f /etc/sudoers.d/90-cloudimg-ubuntu ]; then

mv /etc/sudoers.d/90-cloudimg-ubuntu /etc/sudoers.d/90-cloud-init-users

fi

perl -pi -e "s/ubuntu/$user/g;" /etc/sudoers.d/90-cloud-init-users

fi

if [ '${var.userpw}' == '$(pwgen 12)' ]

then

apt update && apt install pwgen

fi

newpw="${var.userpw}"

echo "$newpw" > /var/log/userpw

fullpw="$newpw"

fullpw+="\n"

fullpw+="$newpw"

echo -e "$fullpw" | passwd $user

##########################

# Install Desktop and RDP

##########################

apt-get update

export DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive

apt-get full-upgrade -yq

apt-get autoremove -y

apt-get autoclean -y

apt-get install -y ${var.desktopenv}-desktop xrdp certbot

##########################

# Configure Certbot

##########################

echo "#!/bin/sh" > /etc/letsencrypt/merge_cert.sh

echo 'cat ${var.var_start}{RENEWED_LINEAGE}/privkey.pem ${var.var_start}{RENEWED_LINEAGE}/fullchain.pem > ${var.var_start}{RENEWED_LINEAGE}/merged.pem' >> /etc/letsencrypt/merge_cert.sh

echo 'chmod 640 ${var.var_start}{RENEWED_LINEAGE}/merged.pem' >> /etc/letsencrypt/merge_cert.sh

chmod 750 /etc/letsencrypt/merge_cert.sh

certbot certonly --standalone --deploy-hook /etc/letsencrypt/merge_cert.sh -n -d vde.${aws_eip.vde.public_ip}.nip.io -d ${aws_eip.vde.public_ip}.nip.io --register-unsafely-without-email --agree-tos

# Based on https://www.snel.com/support/xrdp-with-lets-encrypt-on-ubuntu-18-04/

sed -i 's~^certificate=$~certificate=/etc/letsencrypt/live/vde.${aws_eip.vde.public_ip}.nip.io/fullchain.pem~; s~^key_file=$~key_file=/etc/letsencrypt/live/vde.${aws_eip.vde.public_ip}.nip.io/privkey.pem' /etc/xrdp/xrdp.ini

##############################

# Fix colord remote user issue

##############################

# Derived from http://c-nergy.be/blog/?p=12043

echo "[Allow Colord all Users]

Identity=unix-user:*

Action=org.freedesktop.color-manager.create-device;org.freedesktop.color-manager.create-profile;org.freedesktop.color-manager.delete-device;org.freedesktop.color-manager.delete-profile;org.freedesktop.color-manager.modify-device;org.freedesktop.color-manager.modify-profile

ResultAny=no

ResultInactive=no

ResultActive=yes" > /etc/polkit-1/localauthority/50-local.d/45-allow.colord.pkla

##############################

# Configure Desktop

##############################

if [ '${var.desktopenv}' == 'ubuntu' ]

then

echo "#!/bin/bash" > /tmp/desktop_settings

echo "gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.input-sources sources \"[('xkb', 'gb')]\"" >> /tmp/desktop_settings

echo "gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.app-folders folder-children \"['Utilities', 'Sundry', 'YaST']\"" >> /tmp/desktop_settings

echo "gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.privacy report-technical-problems false" >> /tmp/desktop_settings

echo "gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.screensaver lock-enabled false" >> /tmp/desktop_settings

echo "gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.session idle-delay 0" >> /tmp/desktop_settings

echo "echo yes > /home/${var.firstuser}/.config/gnome-initial-setup-done" >> /tmp/desktop_settings

sudo -H -u ${var.firstuser} dbus-launch --exit-with-session bash /tmp/desktop_settings

rm -f /tmp/desktop_settings

fi

##########################

# Install VSCode

##########################

wget https://vscode-update.azurewebsites.net/latest/linux-deb-x64/stable -O /tmp/vscode.deb

apt install -y /tmp/vscode.deb

rm /var/crash/*

shutdown -r nowUbuntu 18.04 has a “first login” wizard, that lets you pre-set up things like, what language will you be using. I bypassed this with the gsettings commands towards the end of the script, and writing the string “yes” to ~/.config/gnome-initial-setup-done.

Also, I wanted to be able to RDP to it. I’m a bit concerned by the use of VNC, especially where RDP is more than capable. It’s just an apt-install away, so… that’s what I do. But, because I’m RDP’ing into this box, I wanted to prevent the RDP session from locking, so I provide two commands to the session: gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.screensaver lock-enabled false which removes the screensaver’s ability to lock the screen, and gsettings set org.gnome.desktop.session idle-delay 0 which stops the screensaver from even starting in the first place.

Now all I need to do is to figure out where I’m going to store my code between boots ;)

So, in summary, I now have a Virtual Machine, which runs Ubuntu 18.04 Desktop, in AWS, with an RDP connection (powered by xRDP), and a disabled screensaver. Job done, I think!

Oh, and if I’m doing it “wrong”, let me know in the comments? :)

Featured image is “Unnatural Love” by “Keith Garner” on Flickr and is released under a CC-BY-SA license.